COVID-19: Who was failed the most?

- Jinqian Li

- Feb 9, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 31, 2021

Far from being a great leveller, Covid attacked some people more than others. People with learning disabilities are more likely to fall victim to the virus. Jinqian Li takes an inside look at how the safety net is failing the most vulnerable in society.

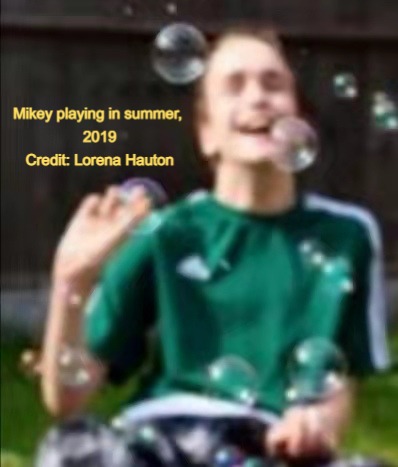

It is July 20th. The morning dragged until Lorena Hauton got in her car and drove towards her son’s house. Now sitting in a small queue of traffic the anxious yet excited mum feels the emotion begin to bubble up, but she gets it in check. She had dreamt of this moment for 10 weeks.

Her 19-year-old son Mikey has been cared for in a residential home because of severe learning disabilities, autism and complex health needs. The last day they were together is, ironically, Mother’s Day. Naturally there was a lot of anxiety around as people spoke of coronavirus and what it would mean in life. At first Lorena didn’t envisage she wouldn’t still see her son. However, the day after government implemented the coronavirus restrictions, she knew this was going to be the case. Mikey has chronic lung disease and needs additional oxygen, so he was one of the many who was told he must shield during the first lockdown.

For Lorena, it physically hurts as this is made worse by how Mikey processes the world around him. His understanding is ‘here and now’, there is no ‘then’ or ‘there’, which takes away the ability to use video calling to communicate whilst they cannot see each other. Before this, the longest they have been apart since Mikey first moved into his new home was only nine days. The umbilical cord was never meant to be stretched this far.

“It’s not right, yet it is right as it is for his safety, but what is it doing to his mental health?” Lorena says.

“Everyday I ask myself, what does he understand? What is he thinking? Does he think I have abandoned him? Does he think I don’t love him?”

Once Lorena was admitted to the room in Mikey's care room, she instinctively called out her son's name. She had to lift the mask momentarily so he could see her full face. Then the heart instantly healed in that moment when she saw Mikey smile, the curve that always straightens her world.

Lorena expected not to be able to control her emotion, but as always, she needed to focus on the needs of her son as she started to realise Mikey has become intensely withdrawn. He lost interest in their old familiar game Matryoshka, most of the time just staring blankly, uncontrollably jerking and shaking. His gait continued to decline with increased bradykinesia and shuffling, falling forward when he was finally able to move. The only one word he could say clearly, a word reserved just for Lorena — ‘Muuummum’, after 70 days in Covid lockdown and no contact, now escaped him.

Lorena says: “It’s been an absolute emotional roller coaster. I daren’t think of if my son becomes poorly what that means. It feels like a bereavement.

“His deterioration didn’t get noticed at all. What if he caught the virus? No equipment to test, no staff has knowledge about it. Guidance has been confusing throughout and has never prioritised the needs of people with learning disabilities.”

Lorena is not alone. According to an analysis of 206 learning disability deaths from the The Learning Disabilities Mortality Review (LeDeR) Programme, almost a quarter (23%) of people who died from COVID-19 had the absence of tools (e.g. National Early Warning Score 2) and equipment (e.g. pulse oximeters) to detect acute deterioration recorded. This has particularly been the case in primary care and community settings.

However, given that people with LD have common communication difficulties, a detecting mechanism is always crucial for assessing their condition. It is especially true under the pandemic when they generally don't have manifest virus symptoms, which makes monitoring deterioration ‘impossible’ without the support of medical tools, as Professor John Newton, director of health improvement at Public Health England (PHE) claimed in a report.

Among 206 death samples of those who died from COVID-19, no one reported a loss of sense of smell or taste, while 56% of them only had slight fever or cough even if in a serious deterioration stage. A small number of them (5%) had no symptoms at all.

Meanwhile, the concerns ‘Support staff not familiar with early recognition and detection of deterioration in health’ are frequently raised as the analysis stated, posing potential risks to people with LD. Based on the LeDeR report, one in ten of samples of those who died from COVID-19 had a sudden deterioration in their condition following a period of apparent improvement, causing ‘avoidable death’ as no preventive plans were prepared in advance from carers. It also discovers that often the subtle signs of some people with LD about Covid deterioration are not always identified within the monitoring tool or algorithm used to prioritise calls to NHS111. Approximately 6% of people with LD who died of coronavirus in the samples were recorded having ‘tiredness’ as a sole symptom, any alert therefore will not be triggered should caregivers not have knowledge of it.

As a result of the lack of equipment and proper training to staff, the neglect of virus deterioration would leave people with LD at greater danger than the public due to the prevalence of underlying diseases. A study from the Department of Medicine in Cambridge University illustrates 90% of people with LD have at least one long-term health condition, with more frequently reported mobility impairment (82%) and respiratory conditions (79%). Over 20% of them are noted as having Down’s syndrome, which could cause people to be 10 times more likely to die from COVID-19 as those without.

Young people are especially disadvantaged under poor healthcare — as the Office for National Statistics reported those aged 18 to 34 with a learning disability are 30 times more likely to die from Covid than others their age.

Mikey is one of the 90% with a substantial underlying health condition.

“The lung disease makes his breathing extremely difficult. It pains me to think that the healthcare services who’re caring for him can’t support and guide him as he needed,” Lorena says.

“Some days I spend ages looking at pictures of my son, either recent or older ones. I watch videos over and over again. They make me happy, but they make me sad and yearn for him.

“Are people with learning disabilities seen as expendable? This is the question I have asked myself throughout the Covid crisis as I have seen people with a learning disability like him be forgotten time and time again.”

The plight of people with LD is never far from view. A new PHE report finds the Covid death rate of people with LD is three to four times the rate in the general population – which soares to six times as high if comparing deaths of people of the same age and sex in the general population.

Dan Scorer, the head of policy at the learning disability charity Mencap, says: “It’s deeply devastating that one of the most vulnerable groups in our society has been hit disproportionately hard by the virus.”

He stresses that the health inequalities people with learning disabilities have already experienced are ‘troublingly underpinning prejudicial attitudes towards care, treatment and judgements about ceilings of care’. In light of the LeDeR report, except for the access to appropriate healthcare, the Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR) decision process is to blame.

Of those who died from COVID-19, 82% had a DNACPR decision. However, LeDeR reviewers noted nearly 40% of the patients’ families have complained that frailty or learning disabilities were, inappropriately, given as a rationale for a DNACPR decision or the decision-making process had not adhered to the Mental Capacity Act. Over 50% of LD nurses surveyed by Mencap said there is a ‘high risk’ of people with a learning disability receiving an inappropriate DNACPR during the pandemic.

Ruth May, Chief Nursing Officer at NHS England, says: “It’s not only illegal but outrageous that a doctor/GP would decide not to save someone just because they have a learning disability. They have the same right to life as anyone else.

“Decisions on people’s treatment that are based on someone having a learning disability are never OK — even one is too many.”

Coping with the pandemic is challenging for all, but this is particularly true for people with learning disabilities, who have even less choice and control over their lives than usual.

Life is unexplainably difficult for Lorena as a mum, however, she has to continue for the one she cares for, the day she could be heard.

“I love Mikey with every breath in my body. I can’t afford to lose this battle.” Lorena says.

List of interviews:

Lorena Jane Hauton November 27th 3pm-4.30pm

Ciara Lawrence, Mencap Ambassador

November 30th 5pm-5.30pm (used in video, not copy)

Daniel Goodley, Professor of Disability Studies and Education at Sheffield University

December 1st 5pm-6pm (used in video, not copy)

Dan Scorer, the head of policy at the learning disability charity Mencap

December 2nd 11.30am-12.00pm

Ruth May, Chief Nursing Officer at NHS England

December 7th 3.00pm-3.30pm

Comments